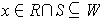

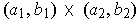

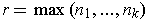

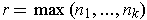

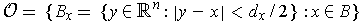

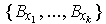

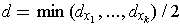

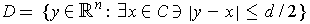

Let

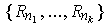

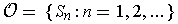

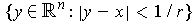

be a collection of open sets, and

be a collection of open sets, and

be their union.

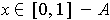

If

be their union.

If

, then there is an

, then there is an

with

with

. Since

. Since

is

open, there is an open rectangle

is

open, there is an open rectangle

containing

containing

.

So

.

So

is open.

is open.

Let

and

and

be open, and

be open, and

. If

. If

, then

there are open rectangles

, then

there are open rectangles

(resp.

(resp.

) containing

) containing

and contained in

and contained in

(resp.

(resp.

). Since the intersection of two open rectangles is an open

rectangle (Why?), we have

). Since the intersection of two open rectangles is an open

rectangle (Why?), we have

; so

; so

is open.

The assertion about finitely many sets follows by induction.

is open.

The assertion about finitely many sets follows by induction.

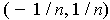

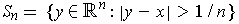

The intersection of the open intervals

is the set containing only

is the set containing only

, and so the intersection of even countably many open sets is not necessarily

open.

, and so the intersection of even countably many open sets is not necessarily

open.

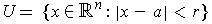

is open.

is open.

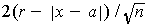

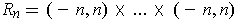

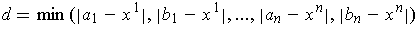

If

, then let

, then let

be the open rectangle centered at

be the open rectangle centered at

with

sides of length

with

sides of length

. If

. If

, then

, then

and so

. This proves that

. This proves that

is open.

is open.

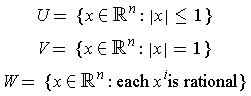

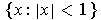

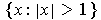

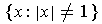

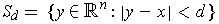

The interior of

is the set

is the set

; the exterior is

; the exterior is

;

and the boundary is the set

;

and the boundary is the set

.

.

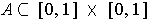

The interior of

is the empty set

is the empty set

; the exterior is

; the exterior is

;

and the boundary is the set

;

and the boundary is the set

.

.

The interior of

is the empty set

is the empty set

; the exterior is the empty set

; the exterior is the empty set

;

and the boundary is the set

;

and the boundary is the set

.

.

In each case, the proofs are straightforward and omitted.

such that

such that

contains at most one point on each horizontal and each vertical line but the

boundary of

contains at most one point on each horizontal and each vertical line but the

boundary of

is

is

. Hint: It suffices to ensure

that

. Hint: It suffices to ensure

that

contains points in each quarter of the square

contains points in each quarter of the square

and also in each sixteenth, etc.

and also in each sixteenth, etc.

To do the construction, first make a list

of all the rational numbers

in the interval [0, 1]. Then make a list

of all the rational numbers

in the interval [0, 1]. Then make a list

of all the quarters, sixteenths, etc.

of the unit sqare. For example,

of all the quarters, sixteenths, etc.

of the unit sqare. For example,

could be made by listing all pairs

(a, b) of integers with

could be made by listing all pairs

(a, b) of integers with

positive,

positive,

non-negative,

non-negative,

, in increasing order

of

, in increasing order

of

, and amongst those with same value of

, and amongst those with same value of

in increasing

lexicographical order; then simply eliminate those pairs for which there is

an earlier pair with the same value of

in increasing

lexicographical order; then simply eliminate those pairs for which there is

an earlier pair with the same value of

. Similarly, one could make

. Similarly, one could make

by listing first the quarters, then the sixteenths, etc. with an obvious

lexicographical order amongst the quarters, sixteenths, etc. Now, traverse

the list

by listing first the quarters, then the sixteenths, etc. with an obvious

lexicographical order amongst the quarters, sixteenths, etc. Now, traverse

the list

: for each portion of the square, choose the point

: for each portion of the square, choose the point

such

that

such

that

is in the portion, both

is in the portion, both

and

and

are in the list

are in the list

, neither

has yet been used, and such that the latter occurring (in

, neither

has yet been used, and such that the latter occurring (in

) of them is

earliest possible, and amongst such the other one is the earliest possible.

) of them is

earliest possible, and amongst such the other one is the earliest possible.

To show that this works, it suffices to show that every point

in the

square is in the boundary of

in the

square is in the boundary of

. To show this, choose any open rectangle

containing

. To show this, choose any open rectangle

containing

. If it is

. If it is

, let

, let

. Let

. Let

be chosen so

that

be chosen so

that

. Then there is some

. Then there is some

portion of the square

in

portion of the square

in

which is entirely contained within the rectangle and containing

which is entirely contained within the rectangle and containing

.

Since this part of the square contains an element of the set A and elements

not in A (anything in the portion with the same x-coordinate

.

Since this part of the square contains an element of the set A and elements

not in A (anything in the portion with the same x-coordinate

works), it

follows that

works), it

follows that

is in the boundary of

is in the boundary of

.

.

is the union of open intervals

is the union of open intervals

such that each rational number in

such that each rational number in

is contained in some

is contained in some

,

show that the boundary of

,

show that the boundary of

is

is

.

.

Clearly, the interior of

is

is

itself since it is a union of open sets;

also the exterior of

itself since it is a union of open sets;

also the exterior of

clearly contains

clearly contains

as

as

.

Since the boundary is the complement of the union of the interior and the

exterior, it suffices to show that nothing in

.

Since the boundary is the complement of the union of the interior and the

exterior, it suffices to show that nothing in

is in the exterior

of

is in the exterior

of

. Suppose

. Suppose

is in the exterior of

is in the exterior of

. Let

. Let

be an open interval containing

be an open interval containing

and disjoint from

and disjoint from

. Let

. Let

be a rational

number in

be a rational

number in

contained in

contained in

. Then there is a

. Then there is a

which contains

which contains

, which is a contradiction.

, which is a contradiction.

is a closed set that contains every rational number

is a closed set that contains every rational number

,

show that

,

show that

.

.

Suppose

. Since

. Since

is open, there is an open

interval

is open, there is an open

interval

containing

containing

and disjoint from

and disjoint from

. Now

. Now

contains a non-empty open subinterval of

contains a non-empty open subinterval of

and this is necessarily

disjoint from

and this is necessarily

disjoint from

. But every non-empty open subinterval of

. But every non-empty open subinterval of

contains

rational numbers, and

contains

rational numbers, and

contains all rational numbers in

contains all rational numbers in

, which is

a contradiction.

, which is

a contradiction.

is closed and bounded.

is closed and bounded.

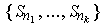

Suppose

is compact. Let

is compact. Let

be the open cover consisting of

rectangles

be the open cover consisting of

rectangles

for all positive integers

for all positive integers

. Since

. Since

is compact, there is a finite subcover

is compact, there is a finite subcover

.

If

.

If

, then

, then

and so

and so

is bounded.

is bounded.

To show that

is closed, it suffices its complement is open.

Suppose

is closed, it suffices its complement is open.

Suppose

is not in

is not in

.

Then the collection

.

Then the collection

where

where

is an open cover of

is an open cover of

. Let

. Let

be a finite subcover. Let

be a finite subcover. Let

.

Then

.

Then

is an open neighborhood of

is an open neighborhood of

which is disjoint from

which is disjoint from

. So the complement of

. So the complement of

is open, i.e.

is open, i.e.

is closed.

is closed.

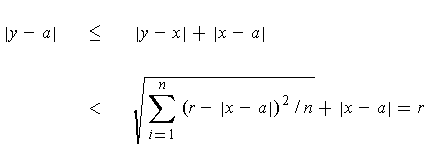

- If

is closed and

is closed and

, prove that there is a number

, prove that there is a number

such

that

such

that

for all

for all

.

.

Such an

is in the exterior of

is in the exterior of

, and so there is an open rectangle

, and so there is an open rectangle

containing

containing

and disjoint from

and disjoint from

.

Let

.

Let

.

This was chosen so that

.

This was chosen so that

is

entirely contained within the open rectangle. Clearly, this means that

no

is

entirely contained within the open rectangle. Clearly, this means that

no

can be

can be

, which shows the assertion.

, which shows the assertion.

- If

is closed,

is closed,

is compact, and

is compact, and

,

prove that there is a

,

prove that there is a

such that

such that

for all

for all

and

and

.

.

For each

, choose

, choose

to be as in part (a). Then

to be as in part (a). Then

is an open cover of

is an open cover of

.

Let

.

Let

be a finite subcover, and let

be a finite subcover, and let

.

Then, by the triangle inequality, we know that

.

Then, by the triangle inequality, we know that

satisfies the assertion.

satisfies the assertion.

- Give a counterexample in

if

if

and

and

are required

both to be closed with neither compact.

are required

both to be closed with neither compact.

A counterexample:

is the x-axis and

is the x-axis and

is the graph of the

exponential function.

is the graph of the

exponential function.

is open and

is open and

is compact, show that there is

a compact set

is compact, show that there is

a compact set

such that

such that

is contained in the interior of

is contained in the interior of

and

and

.

.

Let

be as in Problem 1-21 (b) applied with

be as in Problem 1-21 (b) applied with

and

and

.

Let

.

Let

. It is

straightforward to verify that

. It is

straightforward to verify that

is bounded and closed; so

is bounded and closed; so

is compact.

Finally,

is compact.

Finally,

is also true.

is also true.