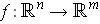

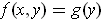

is differentiable

at

is differentiable

at

, then it is continuous at

, then it is continuous at

.

.

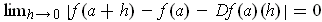

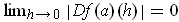

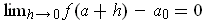

If

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

, then

, then

. So, we need only show that

. So, we need only show that

,

but this follows immediately from Problem 1-10.

,

but this follows immediately from Problem 1-10.

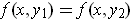

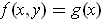

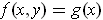

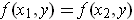

is said to be

independent of the second variable if for each

is said to be

independent of the second variable if for each

we have

we have

for all

for all

. Show that

. Show that

is independent

of the second variable if and only if there is a function

is independent

of the second variable if and only if there is a function

such that

such that

.

What is

.

What is

in terms of

in terms of

?

?

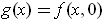

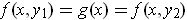

The first assertion is trivial: If

is independent of the second variable,

you can let

is independent of the second variable,

you can let

be defined by

be defined by

. Conversely, if

. Conversely, if

, then

, then

.

.

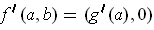

If

is independent of the second variable, then

is independent of the second variable, then

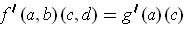

because:

because:

Note: Actually,

is the Jacobian, i.e. a 1 x 2 matrix. So,

it would be more proper to say that

is the Jacobian, i.e. a 1 x 2 matrix. So,

it would be more proper to say that

, but I will often

confound

, but I will often

confound

with

with

, even though one is a linear transformation

and the other is a matrix.

, even though one is a linear transformation

and the other is a matrix.

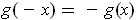

is independent

of the first variable and find

is independent

of the first variable and find

for such

for such

. Which functions are

independent of the first variable and also of the second variable?

. Which functions are

independent of the first variable and also of the second variable?

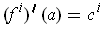

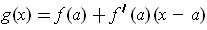

The function

is independent of the first variable if and only if

is independent of the first variable if and only if

for all

for all

. Just as before,

this is equivalent to their being a function

. Just as before,

this is equivalent to their being a function

such that

such that

for all

for all

. An argument similar

to that of the previous problem shows that

. An argument similar

to that of the previous problem shows that

.

.

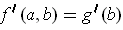

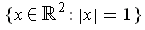

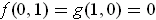

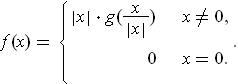

be a continuous real-valued function on the unit circle

be a continuous real-valued function on the unit circle

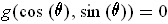

such that

such that

and

and

. define

. define

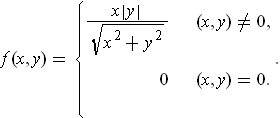

by

by

- If

and

and

is defined

by

is defined

by

, show that

, show that

is differentiable.

is differentiable.

One has

when

when

and

and

otherwise. In

both cases,

otherwise. In

both cases,

is linear and hence differentiable.

is linear and hence differentiable.

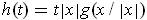

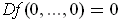

- Show that

is not differentiable at (0, 0) unless

is not differentiable at (0, 0) unless

.

.

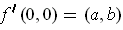

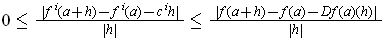

Suppose

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

with, say,

with, say,

.

Then one must have:

.

Then one must have:

.

But

.

But

and so

and so

. Similarly, one gets

. Similarly, one gets

.

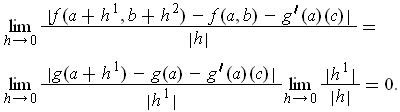

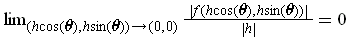

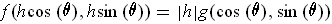

More generally, using the definition of derivative, we get for fixed

.

More generally, using the definition of derivative, we get for fixed

:

:

. But

. But

, and so we see that this just says that

, and so we see that this just says that

for all

for all

. Thus

. Thus

is identically zero.

is identically zero.

be defined by

be defined by

Show that

is a function of the kind considered in Problem 2-4, so that

is a function of the kind considered in Problem 2-4, so that

is not differentiable at

is not differentiable at

.

.

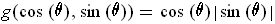

Define

by

by

for all

for all

. Then it is trivial to show that

. Then it is trivial to show that

satisfies all the

properties of Problem 2-4 and that the function

satisfies all the

properties of Problem 2-4 and that the function

obtained from this

obtained from this

is as in the statement of this problem.

is as in the statement of this problem.

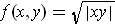

be defined by

be defined by

. Show that

. Show that

is not differentiable at 0.

is not differentiable at 0.

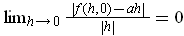

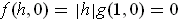

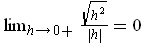

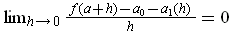

Just as in the proof of Problem 2-4, one can show that, if

were

differentiable at 0, then

were

differentiable at 0, then

would be the zero map. On the other hand,

by approaching zero along the 45 degree line in the first quadrant, one

would then have:

would be the zero map. On the other hand,

by approaching zero along the 45 degree line in the first quadrant, one

would then have:

in spite

of the fact that the limit is clearly 1.

in spite

of the fact that the limit is clearly 1.

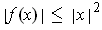

be a function such that

be a function such that

. Show that

. Show that

is differentiable at 0.

is differentiable at 0.

In fact,

by the squeeze principle using

by the squeeze principle using

.

.

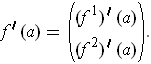

. Prove that

. Prove that

is

differentiable at

is

differentiable at

if and only if

if and only if

and

and

are, and in

this case

are, and in

this case

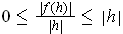

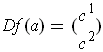

Suppose that

. Then one

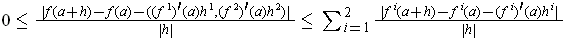

has the inequality:

. Then one

has the inequality:

. So, by the squeeze principle,

. So, by the squeeze principle,

must be differentiable at

must be differentiable at

with

with

.

.

On the other hand, if the

are differentiable at

are differentiable at

, then use the

inequality derived from Problem 1-1:

, then use the

inequality derived from Problem 1-1:

and the squeeze principle to conclude that

and the squeeze principle to conclude that

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

with the desired derivative.

with the desired derivative.

are equal up

to

are equal up

to

order at

order at

if

if

- Show that

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

if and only if there is

a function

if and only if there is

a function

of the form

of the form

such that

such that

and

and

are equal up to first order at

are equal up to first order at

.

.

If

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

, then the function

, then the function

works by the definition of derivative.

works by the definition of derivative.

The converse is not true. Indeed, you can change the value of

at

at

without changing whether or not

without changing whether or not

and

and

are equal up to first order. But

clearly changing the value of

are equal up to first order. But

clearly changing the value of

at

at

changes whether or not

changes whether or not

is

differentiable at

is

differentiable at

.

.

To make the converse true, add the assumption that

be continuous at

be continuous at

:

If there is a

:

If there is a

of the

specified form with

of the

specified form with

and

and

equal up to first order, then

equal up to first order, then

. Multiplying

this by

. Multiplying

this by

, we see that

, we see that

. Since

. Since

is continuous, this means that

is continuous, this means that

. But then the condition

is equivalent to the assertion that

. But then the condition

is equivalent to the assertion that

is differentiable at

is differentiable at

with

with

.

.

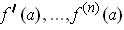

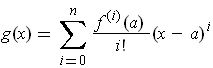

- If

exist, show that

exist, show that

and the function

and the function

defined by

defined by

are equal up to

order at a.

order at a.

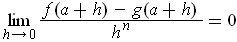

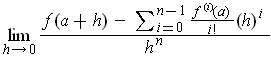

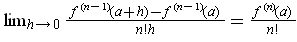

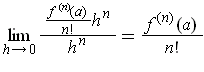

Apply L'Hôpital's Rule n - 1 times to the limit

to see that the value of the limit is

. On the other hand, one has:

. On the other hand, one has:

Subtracting these two results gives shows that

and

and

are equal up to

are equal up to

order at

order at

.

.